"Consciousness can be firmly embedded in biology, based on the fact that all kinds of [demonstrably biological] processes that are not [by themselves] conscious are important for conscious process[ing].”

- David Edelman, PhD, A neuroscientist and a Visiting Scholar in the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences at Dartmouth College

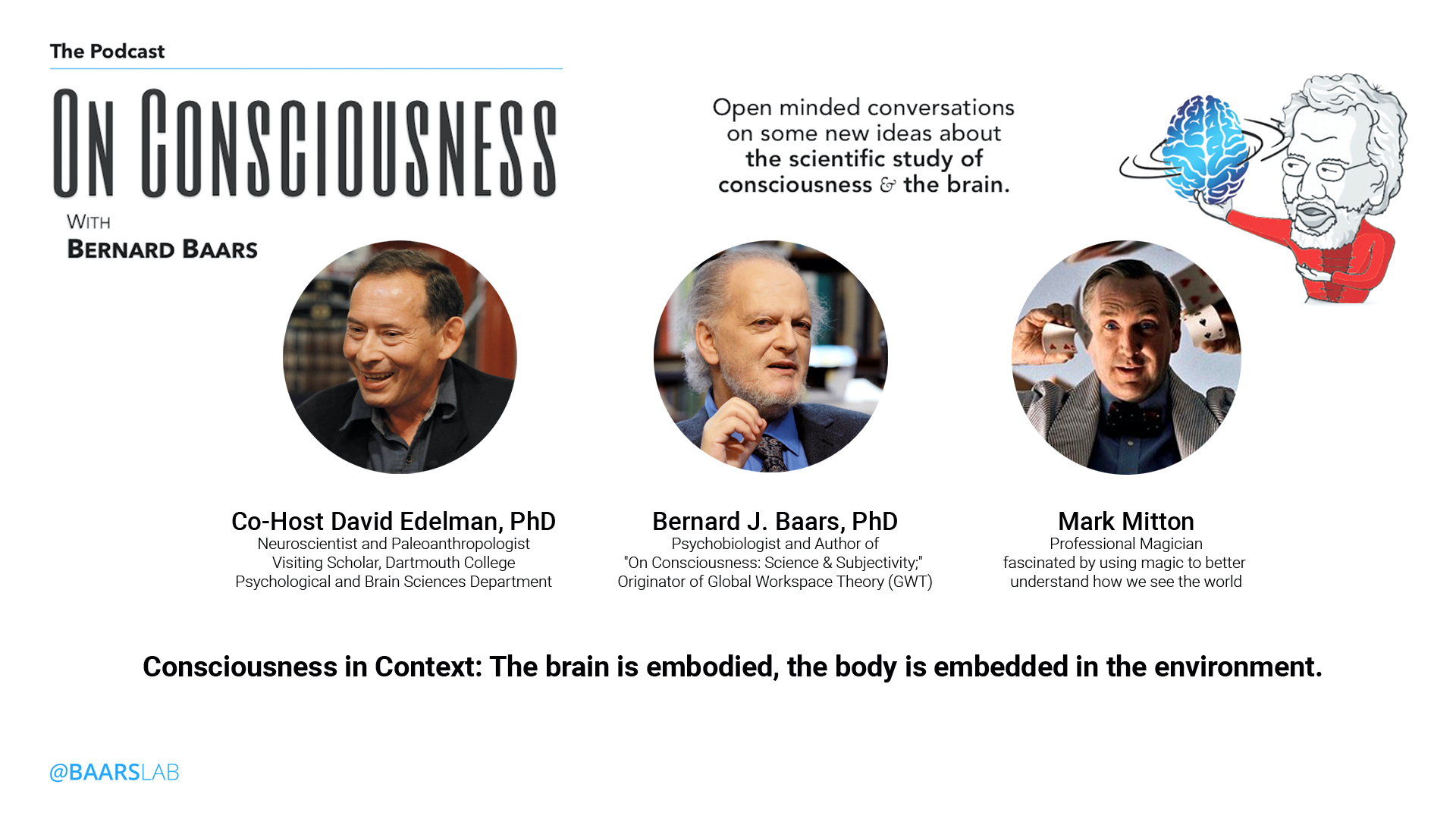

Episode 12: "Consciousness in Context - The Brain is Embodied and the Body is Embedded"

In the 12th episode of ‘On Consciousness,’ psychobiologist Bernard Baars and neuroscientist David Edelman are joined by renowned master of misdirection and sleight of hand, professional magician Mark Mitton, as they consider the problem of consciousness within the larger scope of biology.

Talking Points:

- 00:03 – Introduction by Bernard Baars.

- 02:42 – Mark Mitton introduces himself.

- 04:55 – David Edelman introduces himself.

- 06:47 – David discusses cephalopods and their behavior.

- 09:15 – How is magic connected to consciousness?

- 13:20 – What are the boundaries of one’s knowledge?

- 18:32 – Limitations of brain imaging technologies.

- 21:14 – Perception and awareness.

- 26:05 – How does paleontology compare to hard sciences?

- 32:20 – The biological complexity of individuality.

- 39:20 – How do antibodies interact with antigens?

- 48:14 – Deception beyond language.

- 52:50 – Are simple organisms conscious?

- 01:01:47 - Non-conscious processes.

- 01:05:27 - Is consciousness a biological process?

Summary of the Conversation:

Starting with the example of magic as it has recently been used by some neuroscientists to explore conscious and unconscious processing in the brain, Mitton highlights the problem of reconciling two nomenclatures and the fact that magicians and neuroscientists think about the processes they manipulate and exploit in some very different ways. This leads to a poignant and topical question, first posed by Mitton and then echoed by Edelman: What are the boundaries of our knowledge? Most magicians think of what they do as craft, and in thinking this way, are willing to afford a degree of mystery to the realm in which they ply their craft. But what about neuroscientists? It can probably be said without exaggeration that many neuroscientists are not necessarily comfortable with the limits of their own knowledge.

Baars, Edelman, and Mitton mull over the relatively recent appreciation of the richness of biological complexity and how this must necessarily alter our view of how consciousness and other aspects of natural phenomena can be woven into a unified view of biology. The complexity of myriad processes across all levels of biological organization seems to stymie our best efforts at formulating a grand theoretical framework that integrates all that we observe in nature.

In confronting the problem of biological complexity, Baars makes the point that, at least in the case of consciousness, the role of the individual hasn’t been well understood or appreciated. Once individual variation is taken into account, the notion of what adaptation means at all levels of biological organization changes radically.

Mitton offers the example of the immune response. How does the immune system recognize a foreign invader it hasn’t encountered before — or, for that matter, a chemical compound that has never existed in the history of the planet — and mount a successful defense of the body? The key to an effective immune response is a vast preexisting (and ever diversifying) repertoire of different kinds of antibodies.

Edelman contrasts this with the case of the digital computer, in which the actions of a machine are instructed by an extrinsic program. Though the example of the immune response seems quite far from the problem of conscious brain function, the role of individual variability and selectional interactions — whether between antibody and antigen or brain and the world it perceives — may be common to both biological processes.

The trio consider how we should proceed in conscious science, knowing what we don’t know. Baars suggests that, while a practical scientific approach might avoid drawing absolute lines, it makes sense to first assume that in order to be conscious, an organism must have a nervous system. All three then acknowledge that many of the functional requisites of consciousness have been objects of study for a long time, such as memory. Consciousness not only overlies the neural faculty of memory, it also depends, for what it is and what it does, on memory and other faculties that have been around for tens of millions of years. All kinds of processes that aren’t by themselves conscious are nevertheless critical to conscious processing.

Finally, Baars, Mitton, and Edelman return to the idea that consciousness is fundamentally biological, even if it seems to thrust us into a weird purview in which we need to deal with a material object called the brain that instantiates immaterial thoughts.

In closing, Mitton offers a phrase coined by Gerald Edelman that neatly encapsulates the idea of placing the mind firmly in biological perspective: “the brain is embodied and the body is embedded.”

Get a 40% Discount for your copy of Bernie Baars' acclaimed new book On Consciousness: Science & Subjectivity - Updated Works on Global Workspace Theory

- GO TO: https://shop.thenautiluspress.com/collections/baars

- APPLY DISCOUNT CODE AT CHECKOUT: "PODCASTVIP"

Bios:

Mark Mitton is a professional magician who is fascinated by using magic to better understand how we see the world. In addition to performing at private and corporate events all over the world, and creating magic for film, television, the Broadway stage, and Cirque du Soleil, Mark explores the theme of 'Misdirection' from an interdisciplinary standpoint. He regularly presents on 'Perception' at universities and conferences in North America and Europe, including the Association for the Scientific Study of Consciousness, and has lectured with the late Nobel Laureate Dr. Gerald Edelman on The Neurosciences Institute. http://markmitton.com

David Edelman, PhD: A neuroscientist and currently Visiting Scholar in the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences at Dartmouth College, David has taught neuroscience at the University of San Diego and UCSD. He was Professor of Neuroscience at Bennington College until 2014 and visiting professor in the Dept of Psychology, CUNY Brooklyn College from 2015-2017.

He has conducted research in a wide range of areas, including mechanisms of gene regulation, the relationship between mitochondrial transport and brain activity, and visual perception in the octopus. A longstanding interest in the neural basis of consciousness led him to consider the importance—and challenge—of disseminating a more global view of brain function to a broad audience.

*Watch Episode 12 on Our YouTube Channel!

No comments yet. Be the first to say something!